Conscious Currents: Observing Life Below

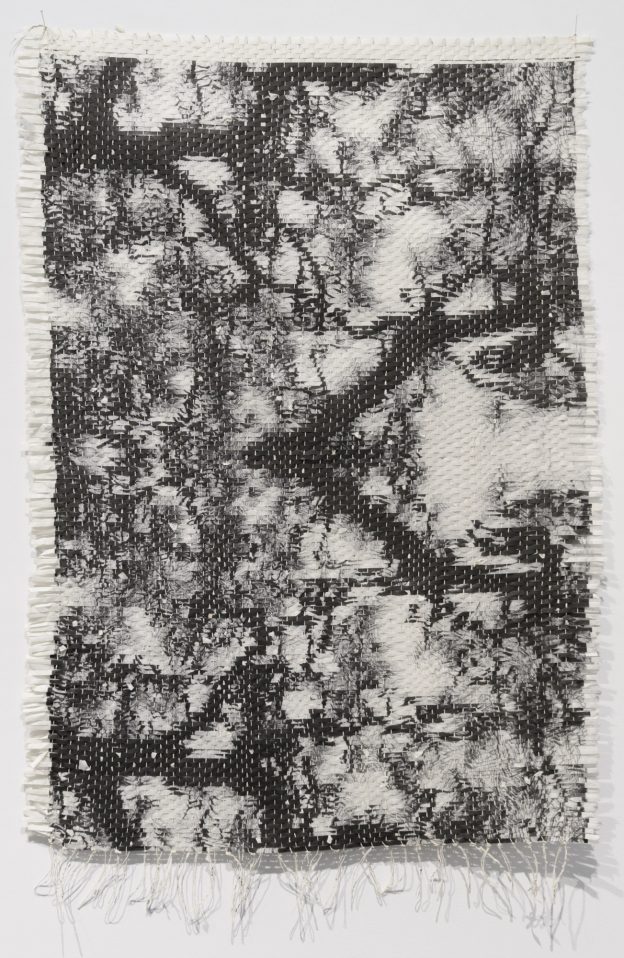

I am interested in exploring our relationships with undersea life. Like many, I watched the film, My Octopus Teacher, and my Instagram feed is filled with people interacting with sharks, seals, and, of course, octopuses. What is going on? How closely does our experience of consciousness align with that of the other beings around us? Somewhere along the way, we—by which I mean the Eurocentric, scientific, capitalist, settler “we”—turned nature into “Nature,” something separate from ourselves. I would like to rethink this habit, exploring ways to adopt a less confrontational approach. (Perhaps this is more aligned with Indigenous perspectives)

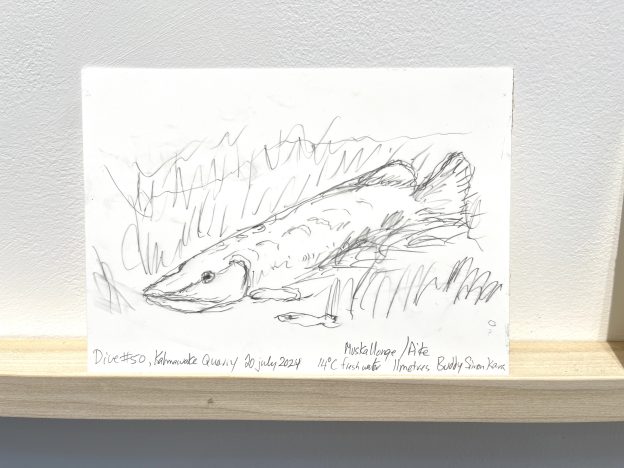

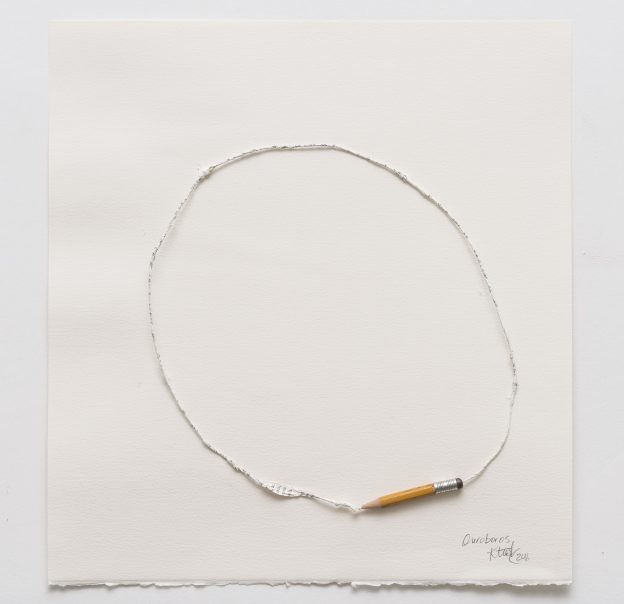

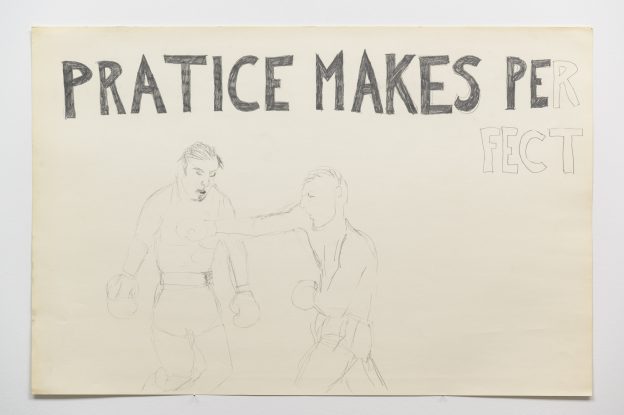

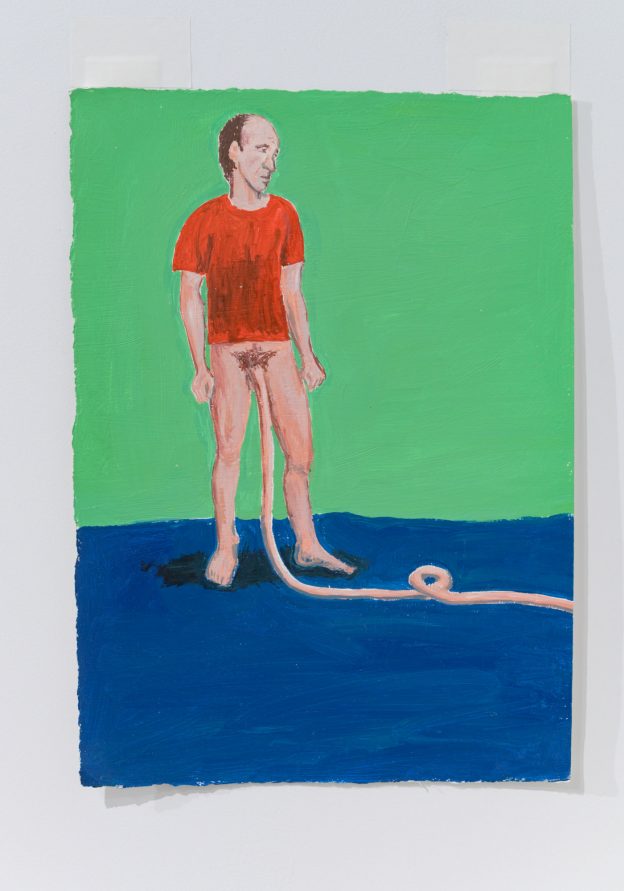

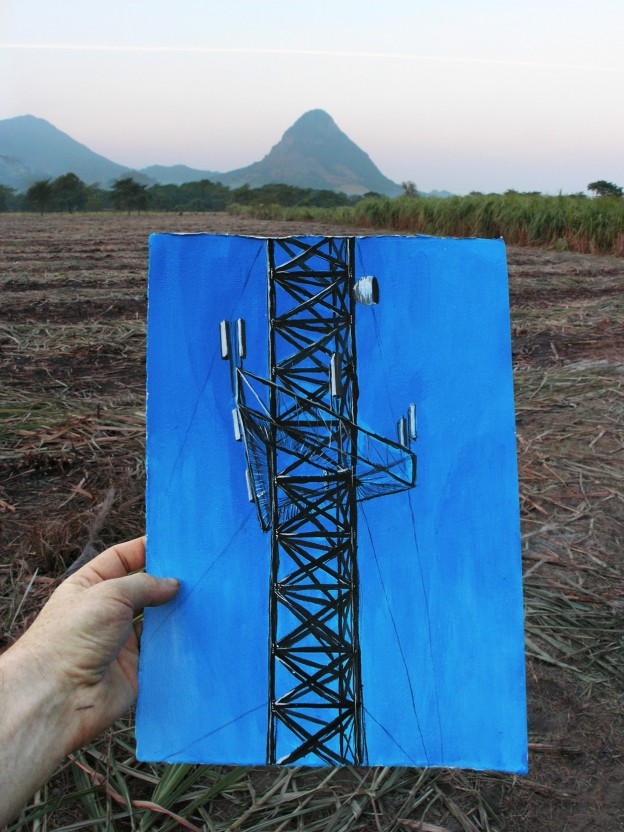

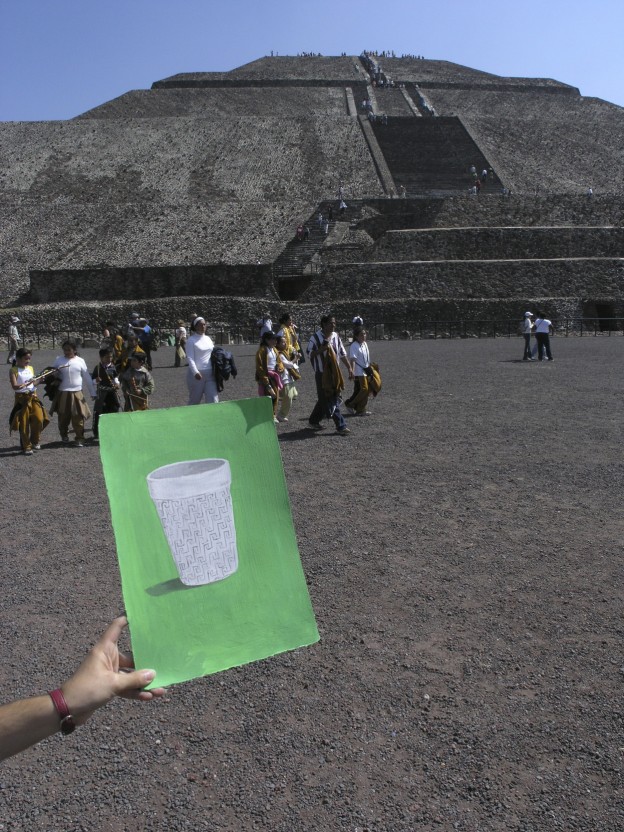

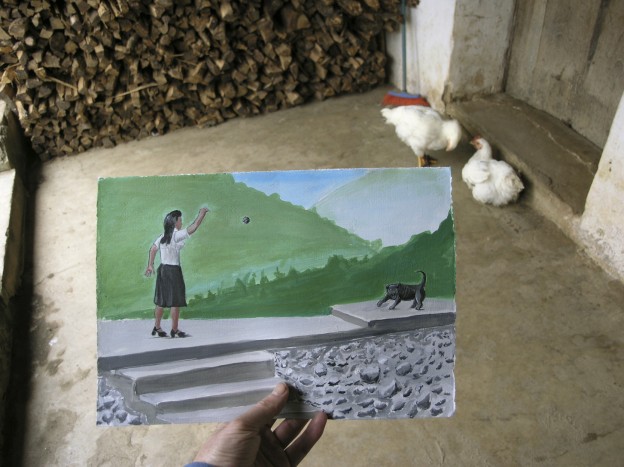

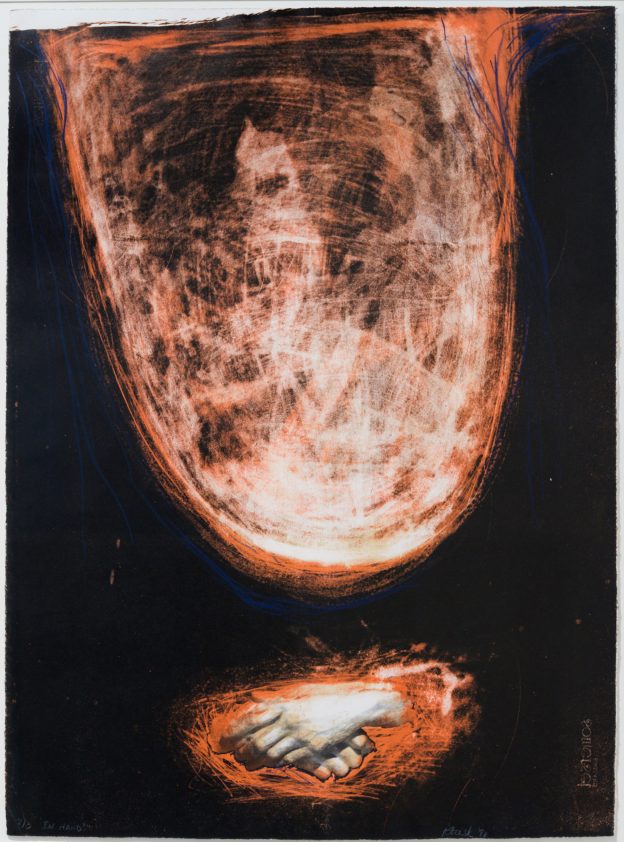

Finding ways to allow our relationship to animals be more visible is part of what this work is about. At first I thought I might perform an absurd action to put our anthropomorphizing tendencies into better relief. I would create “Drawing Lessons for Fish” with the assumption that of course they wouldn’t be interested in what I thought or did. The idea of displaying the chasm of differences in perception would be interesting or at least humorous. But now that I have been down there with them, even for a snippet of time, I don’t think that it was the best approach. They merit more respect. The assumption that they may not be interested makes it more difficult to accept the possibility that animals may have opinions, and that is exactly what I’m looking for.

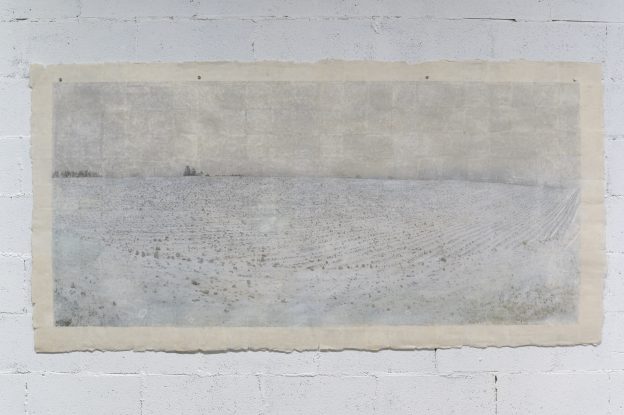

For example, there’s a bass in the Kahnawake quarry that follows divers around, staying just behind their heads and watching where they look. If you point a flashlight at a crayfish in the weeds, it will go over to investigate. This behaviour doesn’t seem random—it’s taking advantage of the diver’s presence to achieve its own goals. Perhaps it’s purely utilitarian: the diver’s air bubbles help oxygenate the water, making the fish feel more energized, and the divers also stir up the bottom, potentially exposing hidden prey illuminated by the flashlight. In this way, the bass is actively benefiting from the interaction, using the diver’s presence to its advantage. However, what if the fish just liked a particular divers company, thought the bubbles were fun, or the flashlight was cool? Maybe it prefers divers who are using the BigBlue VTL13500P-MAX, a 13,000 lumen light to the Kraken NR-1000, a much more modest underwater light.

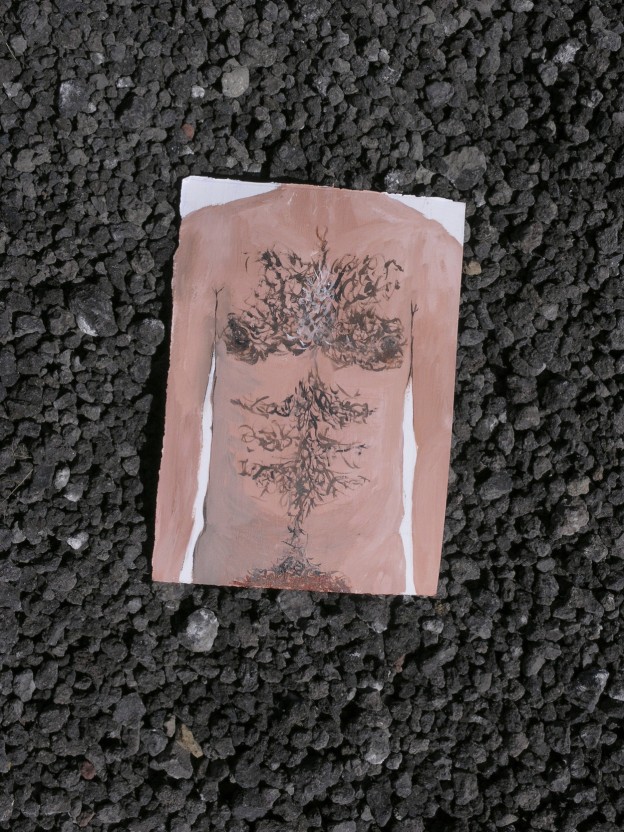

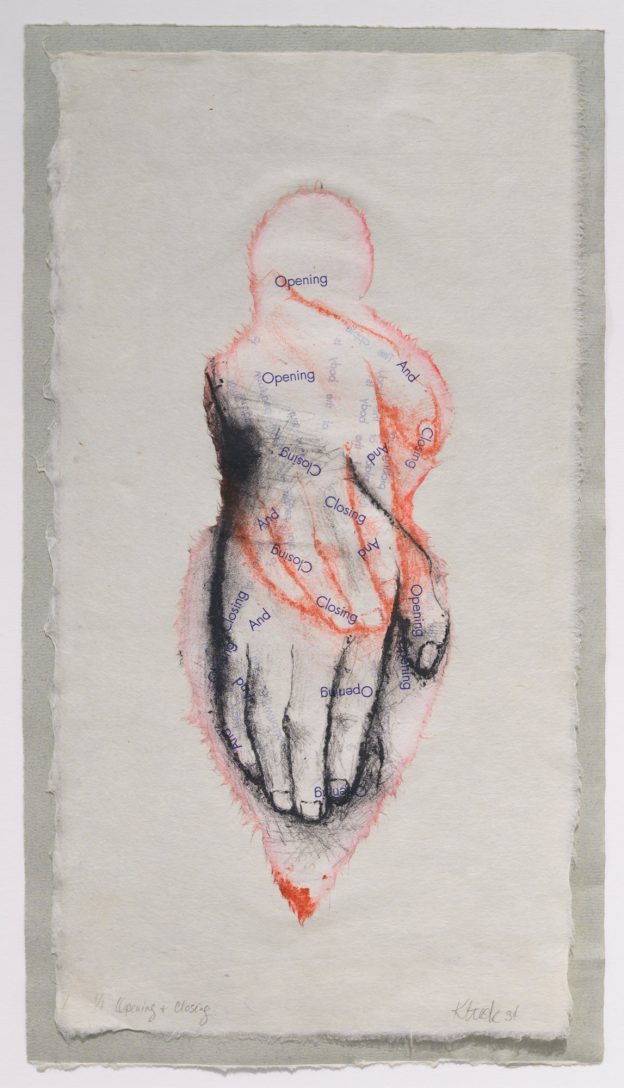

In Michael Pollan’s book The Botany of Desire, he suggests that apple trees have trained us to hybridize them, eat their fruit and plant more of them. This suggests we are not in as much control as we think we are. If I accept this, then it’s not a big stretch to imagine that all kinds of animals might also try to influence us to achieve their own goals. As the project stands now, I make drawings of the underwater life I encounter and look for the animals’ reactions. So far, the results are inconclusive. For example, when I showed an octopus a drawing of itself, it built a wall of rocks, making it clear it didn’t want to be disturbed. However, it may not have been responding to the drawing, but rather to my presence. This relationship did not have enough time to build any trust.

Paul Litherland

November 2024